We’re a few weeks late to the party on Trump’s cabinet pick album drop, but we hope now the dust has settled a bit we can offer our considered thoughts from our corner of the internet.

Robert Francis Kennedy Jr. is an environmental lawyer turned American politician, who was recently nominated by Trump to lead the Department of Health and Human Services. The role will place him as a key adviser to the president on matters of public health, and gives him oversight of organisations like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Given his tendency towards conspiracy theory and lack of public health qualifications, he was recently the target of an open letter signed by 77 Nobel laureates opposing his confirmation into the role.

Who is Robert Francis Kennedy Jr.?

RFK Jr., as he’s familiarly known, made waves as an environmental lawyer from the 1980s into the early 2000s, during which time he is widely credited with helping clean up pollution in the Hudson River, standing up for the rights of indigenous, minority and working class communities and criticising the US military for its environmentally damaging activities. However, despite having no medical credentials, he began to weigh in on vaccines and other public health issues in the mid-2000s.

Despite recent attempts to sanewash him, historically RFK Jr. has been widely criticised for his plethora of unscientific views on public health decisions, with many, more qualified people levelling accusations at him which range from promoting vaccine misinformation to public health conspiracy theories. Some have gone as far as to suggest his presidential endorsement could reduce vaccination rates and bring back diseases like measles and whooping cough.

Just to contextualise things, here’s a brief greatest hits catalogue (for more of his B-sides, see here) of his most egregious, least evidence-based takes:

For 20 years, he relentlessly promoted of the now-widely debunked theory that autism comes from vaccines. This earned him a place in The Disinformation Dozen—a report put out in 2021 showing how RFK Jr. and 11 others were responsible for almost two thirds of vaccine misinformation shared on social media earlier in the same year.

In 2023, he explained how the Covid-19 virus was targeted to attack Caucasians and black people based on genetic differences between races. In response, Prof Melinda Mills at Oxford University’s Nuffield Department of Population Health stated: “The claims of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. are very damaging given they do not follow scientific evidence. As many credible peer-reviewed Covid-19 studies have shown, differences in Covid infections and deaths between socioeconomic and ethnic groups is related to inequalities, deprivation and living in larger or intergenerational households.”

Building on the 2015 Alex Jones “chemicals in the water that are turning the friggin frogs gay” conspiracy theory, RFK Jr. repeatedly shared his unfounded idea that the herbicide atrazine in the water supply is turn children gay and trans throughout 2022 and 2023. Though exposure to the chemical in frogs has led to them changing from male to female, there’s no evidence that this can be extrapolated to humans, not to mention the fact that sex, gender identity and sexual preference are not the same thing.

In a conversation with Elon Musk in 2023, RFK Jr. also suggested a link between school shootings and the introduction of the antidepressant Prozac, despite no scientifically credible evidence to support this.

He has claimed multiple times, despite overwhelming scientific consensus to the contrary, that HIV does not cause AIDS.

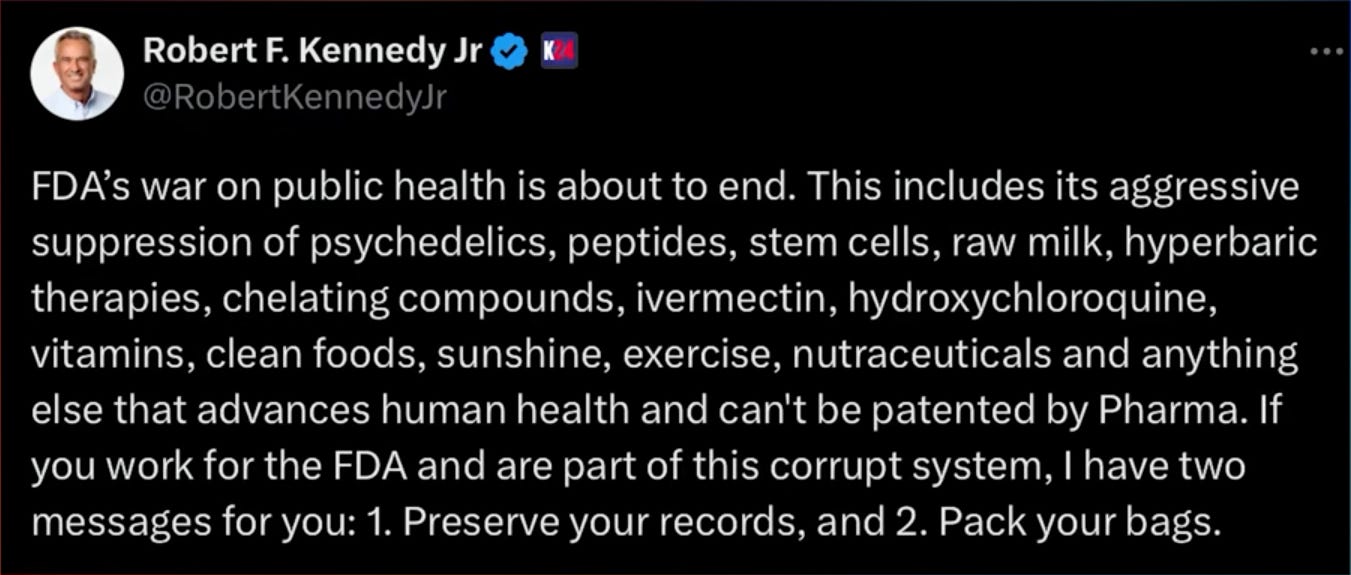

Anyone with a relative who really got into QAnon over the pandemic might have heard some of these takes; RFK Jr. certainly plays to those caught in the overlapping communities of the terminally-online conspiracy theorists and crunchy, wellness social media types. But unlike our MAGA uncle, RFK Jr. is now set to preside over some serious levers of public health power. In October 2024, he had this to say about public health and the FDA (those of you playing wellness-influencer buzzword bingo can pull out your scorecards now):

RFK Jr has quite the shopping list here—but for the sake of brevity, and to spare us the wrath of an online army of perineum sunners (don’t look it up), we’ll just be focussing on psychedelics in this article.

Are psychedelics being “aggressively suppressed”?

In cases where claims are being made of an uneven playing field, we usually find it useful to follow the money. Aggressive suppression usually requires aggressive funding, and given the amount of cash sloshing around the psychedelic wellness industry right now, it can sometimes be hard to spot the stronger currents and those trying to swim against them.

This year states like Florida, North and South Dakota rejected weed legalisation at the ballot box, and Massachusetts did the same for psychedelics. Some have suggested more permissive states like California, New York and Oregon have formed case studies of poorly implemented weed and shroom legalization, which, after a hopeful decade or so of relaxing state drug laws, has shown voters that ending the war on drugs might not be as simple as proponents suggested. Interestingly, these rejections passed in spite of considerable campaign spending to get the bill across the line, as a quote from the link above states:

“The pro-legalization camp in Florida, backed by the massive cannabis company Trulieve, spent nearly $150 million, more than any prior recreational marijuana campaign. The Yes on 4 campaign in Massachusetts spent just $7 million, but that was still 73 times more than the opposition.”

While we’re talking about the money fuelling psychedelic hype, it might be worth drawing attention to the four PR firms hired to help Lykos therapeutics in the wake of their MDMA and PTSD trial setback with the FDA earlier this year. As Jules Evans, the author of the Ecstatic Integration Substack writes:

The aim, according to one source, is to provide enough ‘political cover’ for the FDA to let them disregard the advice of its advisory committee and approve Lykos application for MDMA-assisted therapy in August.

If this source is to be believed, the PR campaign was not successful, as the FDA upheld its decision and called for further Phase 3 clinical trials before approval would be granted. Such requirements for additional testing are commonplace in drug development history, and are typically done in cases where the condition the drug is targeted by may be associated with especially high risks—such as PTSD-induced suicide in veterans. Setbacks like this can be costly for pharmaceutical companies and their shareholders looking to make a return on investment, but it would be pretty ghoulish to put patient safety ahead of profits. The pharma industry has more than its fair share of these ghouls but unlike non-psychedelic drugs, there’s rarely been such a large crowd of onlookers to a drug’s approval process—all potentially ready to be mobilised in the court of public opinion by some savvy PR firm.

Bobby Kennedy Jr. re-enters the picture here as well, as he has also been documented amplifying open letters against organisations who gave evidence against the Lykos MDMA trial to the FDA, ultimately resulting in death threats being made to those involved. Though specific individuals’ names were ultimately removed from the open letter, they were up long enough to attract plenty of the wrong sort of attention.

Money aside, how’s the psychedelic movement looking right now?

If there’s one word to describe today’s psychedelic movement, it’s multifaceted. Though some might argue it’s always been that way, the recent thrust of psychedelics into mainstream consciousness through a growing clinical trial base, as well as popularisation through Michael Pollan’s How To Change Your Mind, there’s a greater diversity of thought and a lot more to form an opinion around.

Back in the 1960s, despite the shadowy influence of the CIA’s MKUltra program, psychedelics were generally associated with the anti-war, hippy counter culture, with figureheads like Allen Ginsberg and Timothy Leary promoting them as a tool for enacting world peace. Jump to today, and it’s a little naive to think that psychedelics fit exclusively within a progressive, left-leaning antiauthoritarian mindset, or that they might be used to turn people on to that way of thinking—despite people like climate activists and psychedelic researchers still holding out hope. We’ve now seen enough media coverage of the conspirituality mongering, QAnon shaman types of the cosmic-right to know that psychedelics can apparently fit coherently within many political narratives. A more nuanced view considers psychedelics as non-specific amplifiers or “politically pluripotent“, in that they intensify some of the previously held beliefs and mental processes of whomever is taking them.

Some would argue that one of the goals of the therapist in psychedelic therapy is to guide participants away from negative mental processes and towards ones that can alleviate their suffering. Amongst early patient groups groups targeted by psychedelic therapy were the depressed and the anxious—such as veterans suffering from PTSD and cancer patients struggling with end-of-life anxiety. While motivated partly by need, the choice of such groups were also strategic, to help drugs like LSD, weed and MDMA gain favour with a mainstream, more conservative audience. As early as the 1990s, the founder of MAPS, Rick Doblin, explicitly stated a comms strategy to “illustrate the potential benefits to even the most conservative members of our society of the resumption of research into psychedelic drugs and marijuana” of which veterans were a key part. Regardless of how you feel about that choice, this strategy ultimately worked, and there is now clearly a more diverse set of political and business voices weighing in on psychedelics.

FDA malice, incompetence, or just real-world challenges?

A potentially large hurdle for psychedelic therapy to overcome is trial design requirement imposed by the FDA. As we’ve talked about before in the context of this year’s FDA rejections of the Lykos MDMA trial, making sure clinical trial participants and researchers studying them are "blind" to who’s in which arm of the trial (e.g. active drug or placebo) is crucial to determining the drug’s true effects. Another criticism levelled at the trial was that 40% of participants had previously tried MDMA. The problem with this is that by including psychedelically experienced participants in a trial, you increase the chances of unblinding. By allowing people on a study who are open to recreational experiences (or those desperate enough to seek underground psychedelic therapy), you’re also recruiting from a patient population who are more likely to rate such an experience as positive. This is a big source of potential bias.

The requirement for so-called “psychedelically naive“ study participants presents a unique problem not faced by non-psychedelic drug development. Few people are rushing out to get their hands on drugs developed by pharmaceutical companies that have yet to be tested, and even if they were the barriers to doing so are too great. With psychedelics, people can grow their own shrooms or procure MDMA and LSD relatively easily. This means that if FDA requirements for naive trial participants stands, the currently growing underground scene of psychonauts are actively removing trial candidates from the potential pool of trial participants. It’s not just us born-again recreational drug takers that are spoiling trials; breathless media hype of psychedelics as a cure-all also might sow seeds of expectancy in those who have never tried psychedelics.

This creates somewhat of a dilemma; either the FDA keeps these requirements and researchers find their well of participants running drier as more people try out psychedelics, or they loosen this requirement, which would mean not holding psychedelics to the same regulatory standards as other drugs. We’re not here to set recreational users against those experiencing mental distress, but it’s clear that neither option ideal for those who could derive benefit from psychedelics in a medical context.

Finally, other healthcare bodies around the world might be a little lukewarm to the promise of psychedelic-assisted therapy, as it currently stands. A recent Cochrane review of psychedelic-assisted therapy for treating anxiety, depression and existential distress in people with life-threatening diseases found very few high quality clinical studies of a combination of therapy with psychedelics like psilocybin (three studies) LSD (two studies) and MDMA (one study), and concluded that that the evidence for their efficacy was “very uncertain” across a range of parameters, and that more high quality studies were needed. Cochrane is a well regarded British non-profit that produces systematic reviews of medical literature, and is used by global care providers and decision makers. A underwhelming review would undoubtedly have effects on those considering incorporating psychedelic assisted therapy treatment programs, as they are currently designed, into their country’s medical systems.

Will RFK Jr. fix things stateside?

This brings us nicely back to RFK Jr. and his vow to end the “FDA’s war on public health.“ The FDA is far from perfect, and has been widely and repeatedly criticised for both being over- and under-regulatory, as well as being too easily bought and sold by pharmaceutical companies (we’d love to dig more deeply into these claims, but we’ve blasted past our target word-count already!). Even setting those criticisms aside, it’s pretty fair to say that as a federal agency responsible for regulating a ludicrous amount of products in one of the worlds biggest countries, it might be spreading its expertise pretty thin.

But given RFK Jr.’s decades-long record on being easily swayed by conspiracy theory and ignorance of credible evidence, we aren’t particularly hopeful that this man in particular is sufficiently qualified to bring changes to the FDA that are in the best interests of public health. Conspiratorial talk of “aggressive suppression of psychedelics” and threats to shake up the system may do little to protect patients, and risk opening the door further to corporatisation, lower standards of care and even instances of neglect and abuse. Furthermore, spreading rhetoric that frames those working for the FDA as deliberately hostile to the public interest, risks painting a target on people’s backs—and as current events have showed us, there are people out there all too willing to pull the trigger.

Imagining a better future

Beyond all of these issues, false dichotomies of underground/mainstream, recreational/medicinal, healthy/unwell may seriously limit our conception of the real promise of psychedelics, which if truly embraced might have incredibly transformative ripple effects throughout society. It’s not so much that psychedelics will transform our future, but a transformed future might include a completely different conception of many aspects of our life, psychedelics included.

Many of us in the psychedelic community are excited to see their drugs of choice finally gain some medical credibility. A while back we felt similarly, like the unfair stigma of dropping a tab of acid and sitting in a dimly lit room while our minds exploded into cosmic space had finally been lifted—because real scientists were using these compounds to alleviate real suffering. But if you’re like us, cheering for psychedelics involves acknowledging that while it’s important to find better ways of treating a growing number of people struggling with their mental health, it can also be simultaneously true that it’s also just nice to get a little high sometimes, and that those in either camp shouldn’t be pitted against each other.

We don’t intend to be too glib here—we acknowledge there’s a big difference in the needs and expectations of people having a fun Friday night at a friend’s house, and those stuck in mental conditions and patterns of serious psychological distress. There’s a large and vocal crowd of people from the former camp passionately advocating for the latter, but we need to remember it’s mentally unwell people we should be supporting—not just our favourite drugs. We think that this should mean holding psychedelic therapy to the same standard as all other forms of mental healthcare, but finding creative ways to address the unique ways psychedelics weave our world together.

"We think that this should mean holding psychedelic therapy to the same standard as all other forms of mental healthcare." The problem is these substances are nothing like other forms of mental healthcare. Attempting to force them into the same box will only confound and confuse the process even more.