Magic mushroom strains aren't that different from each other, says science

A cube is probably a cube, with some exceptions.

One of the most common questions new growers ask us is “which strain should I start with?” Between the often bewildering choice presented by online vendors and online arguments over which is the “best” mushroom strain, you could easily drive yourself to the brink of insanity—or at least be hit with a heavy case of decision paralysis. If you’re anything like us you might be wondering: where’s the evidence?

Up until recently there was very little, but before we talk about that let’s explore why these waters have been so muddy for so long.

If you’ve spent any amount of time in online magic mushroom growing communities of the last 25 years, you will have undoubtedly seen folks arguing over the statement “a cube is a cube”. For those less familiar, this statement stands in opposition to those who claim particular strains of commonly cultivated magic mushrooms (usually Psilocybe cubensis) have distinct psychedelic effects, or differences in their cultivation parameters. “A cube is a cube” flatly rejects these claims, stating that there’s little difference between strains like B+, Golden Teachers and Z-strain (to name a just few).

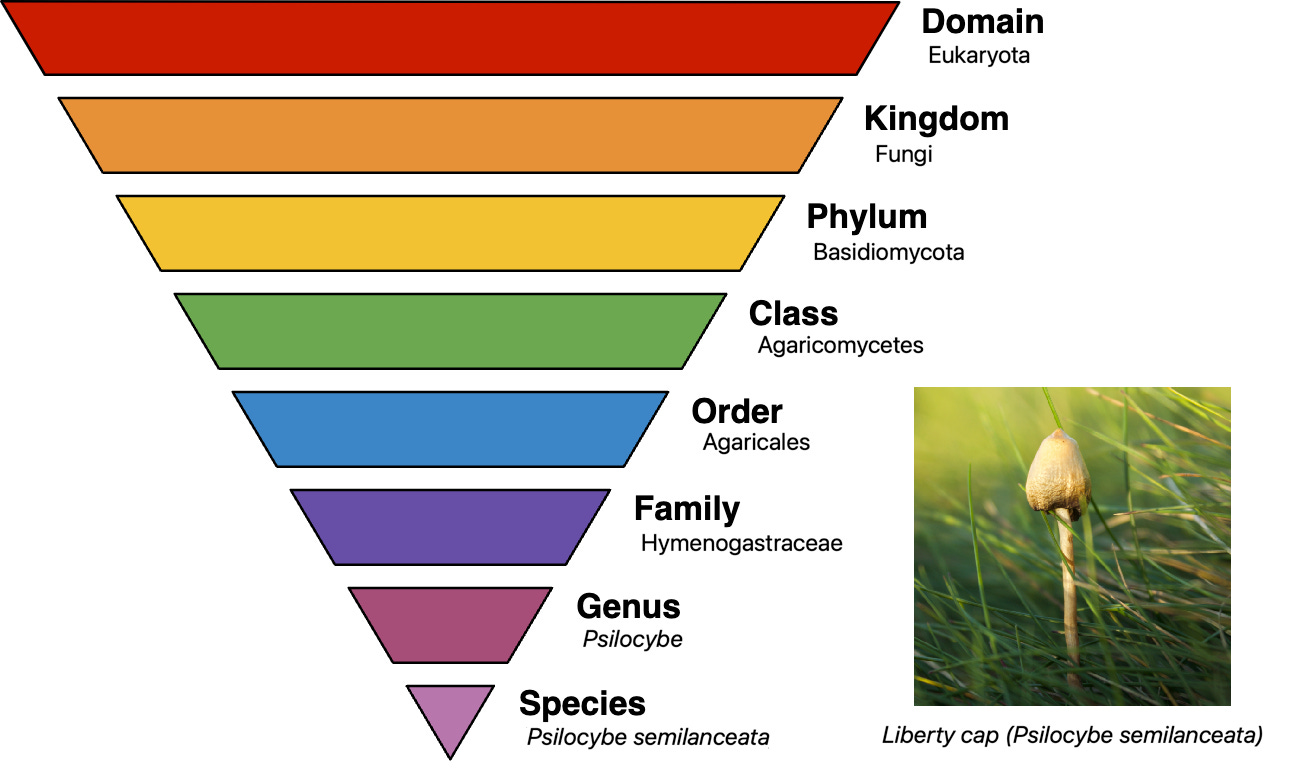

But what is a strain? It’s worth clarifying at this point the difference between between strains and species. Species, generally speaking, is the most basic unit in the hierarchy of taxonomy (remember high school biology? Us neither) or, the largest group of related creatures that can make fertile offspring. Essentially, the classification of species draws a ring around a group of living things that can make babies with each other, who in turn can make babies of their own. This idea of species typically excludes hybrids which are the result of cross-species adult-cuddling sessions, like the mule (horse x donkey) or the liger (lion x tiger), which are usually infertile and therefore represent a genetic dead end. Those talking about species usually refer to their “specific name”—the two part latin name that goes “genus” (the level above species), followed by “species”. In the case of magic mushrooms, most fall into the genus Psilocybe, with specific species including Psilocybe cubensis, Psilocybe cyanescens and Psilocybe mexicana.

We could get a lot more in-depth in to the flawed idea of species, and how fungi in particular challenge this whole concept, but we’ll save that for another article. For now the bottom line is, if animal, plant or fungi is part of the same species, then they’re all closely related enough to fuck, flower or fruit their way into future generations.

When it comes to strains, things get a bit less clear and a bit more socially constructed. Strains, sometimes called clones or varieties, represent the level below species. The term is best understood in the microbiological sense, where strains represent genetically stable colonies of fungi, bacteria or viruses are used to reduce variability in experiments or to produce predictable outputs (such as the same batch of beer over and over again). While different groups of biologists may define strains slightly differently, in the case of magic mushrooms genetic stability is the key concept holding everything together. This means that a true strain should be a genetic clone isolated from agar, and is crucial for ensuring that when you say “Golden Teacher” you mean a fungi with the exact genetics as when someone else uses the same name. So for example, if someone claims “Z-strain is great for new growers as it’s contamination resistant” they might only be talking about their specific experience with something they’re calling “Z-strain”—your results may vary considerably from this.

In the real world however, it’s not always like this—as there’s no test of origin or standardised procedure for producing mushroom strains, and anyone can call any old mycelium Golden Teacher. Due to the clonal nature of true strains, anyone giving you spores of Golden Teacher is not giving you the exact same Golden Teacher they grew, or if we take this analogy back far enough, the same Golden Teacher grown by the grower 20 people up the cultivation chain. This is because as spores intermingle, they produce random genetic combinations and obviously differ genetically from their parents, grandparents or great-grandparents. Applying this to a relatable human analogy, your family and friends might say you have similar qualities to your parents or grandparents, but nobody’s claiming you’re a clone of them—except maybe your one weird uncle who got really into conspiracy theories over the pandemic.

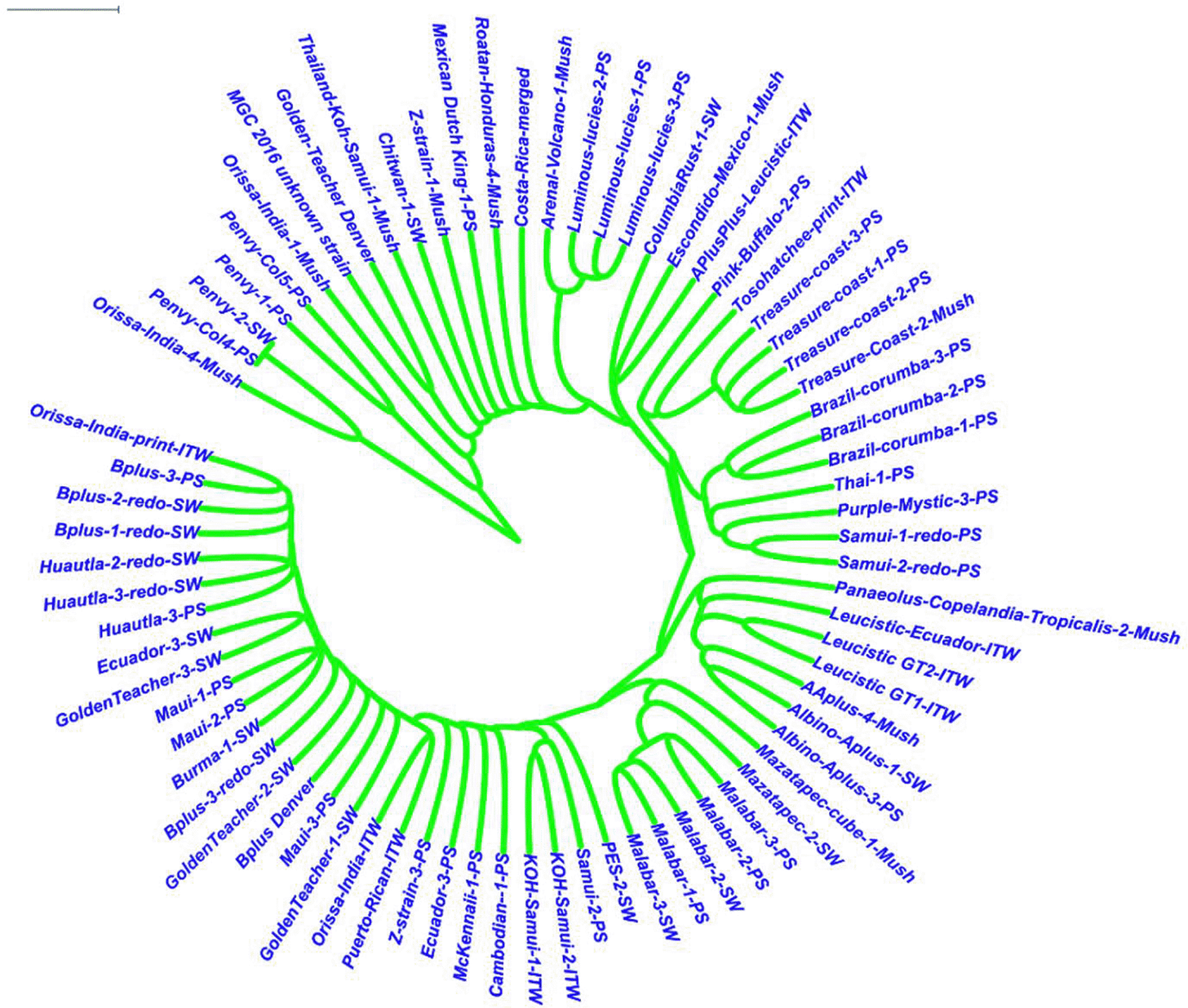

The lack of genetic test for a strain, combined with the fact spore prints easily can be mislabelled, makes the picture suddenly a lot fuzzier. While you and I may say “Golden Teacher” to each other, at present there’s just no way to know for certain that we’re talking about the same thing. This idea is somewhat supported by data. Back in 2021 a genetic study of 81 different popular Psilocybe cubensis strains across four vendors (Sporeworks, Premium Spores, Mushrooms and Inoculate The World) found that while groups of strains (multiple “versions” of B+ or Treasure Coast for example) sold by a single vendor were usually genetically similar, this similarity reduced when the same strain was analysed between vendors. If the concept of strain was as stable as some would have you believe, the analysis would show for similarity at the strain level first, with vendor coming in second or third. Rather than suggesting these vendors don’t know their stuff, these results just highlight that even with the best quality control systems in place, the strain names each vendor allocates to their collections might be impossible to place onto single unified “strain map.”

This means that even empirical measures of potency between strains, such as the excellent Hyphae Cups put out by Oakland Hyphae (check out their Substack -

), are potentially built on muddled origin stories for every sample submitted under a given strain name. The graph below shows a selection of such results, and while at first glance (not withstanding provenance issues) it may appear that there is a difference between strains—take a look at the thin vertical lines sprouting from the top of each bar. These are called error bars and roughly indicate the how certain we are that the measurement is accurate, with larger bars indicating lower certainty. Errors bars that overlap are generally a sign that there’s little evidence in the dataset that there’s a consistent difference between categories—in this case, strains.While most growers can’t visually tell strains like Golden Teacher and B+ apart, even an untrained eye can pick out distinct strains like Penis Envy and Enigma. The difference with some strains is that they have been carefully bred and cloned, with the distinct intention of preserving a particular trait, such as potency. The stories of Penis Envy and other carefully-cultivated strains are fascinating examples of the hard work and effort some growers put in to preserving a particular lineage of interest.

This led some to caveat the oft-repeated phrase “a cube is a cube—except for Penis Envy”, given so many anecdotal reports of trips that were more intense than expected on this enigmatic mushroom strain. Looking at the Hyphae Cup data above, however, it seems that although Penis Envy tends to have a high psilocybin content, it’s not hugely different from other strains analysed. The graph also shows that Penis Envy was one of the most commonly submitted mushrooms for testing, representing around half of all samples analysed. It may be that although the “true” Penis Envy from the early 1980s may have caused intense trips, subsequent breeding from the original strain an unavoidable genetic drift, may have pulled its potency back to that of just another cube*.

A more recent 2023 study compared the genetic diversity and relatedness of 86 commonly cultivated strains, as well as 38 wild culture samples isolated exclusively from Australia. The researchers found a high degree of relatedness between many of the common strains, and a low genetic diversity when compared to the wild Australian isolates. They also note many strains whose names indicated provenance (Amazon, Burma, Cambodia, etc) had a high degree of genetic similarity between each other. As well as lending credibility to the “cube is a cube” argument, this research indicates that either the process of domestication through home magic mushroom growing reduces the genetic diversity of strains isolated from different areas of the globe, or the claims around geographic origin for these strains are dubious.

As well as lending credibility to the lack of significant difference between strains, the work of Alistair McTaggart and his colleagues points to the possibility that domestication of Psilocybe cubensis may have caused it to lose traits such as contamination resistance, that would be desirable to today’s growers. We often don’t consider how our historical attempts to bend the natural world to our own will create unique evolutionary pressures, that can drastically change a once-wild species. In both the plant kingdom, as well as in animals like dogs, common and distinct changes in a variety of characteristics have emerged as the result of domestication—something that’s termed domestication syndrome.

Many of the historical magic mushroom cultivation techniques (dating back from the McKenna’s 1976 Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide, to our book today) rely on highly-uniform, ultra-sterile, laboratory-style techniques that aim to obliterate contamination. While this is a proven method for success, it also removes the stresses of factors like contamination that a wild mushroom has to battle with on a daily basis. Following the “use-it-or-lose-it” theory of evolutionary adaptation, our pampered little Psilocybe cubensis now has all the contamination tolerance of a glass of milk left out of the refrigerator on a warm day. Many growers joke about Psilocybe cubensis’ terrible contamination tolerance relative to other species, so such a theory of a mushroom species that’s become highly domesticated might not be that far out.

So how do we get around this? For a start, new growers shouldn’t stress over which strain is perfect for beginners—they’re all pretty similar. Just pick a strain you like the name of and jump in to growing it. Also, be wary of those making claims about strains that have a distinct high, or “are perfect for microdosing”—until we get better data on things like the entourage effect, most of this is just marketing. Further highlighting the skewed obsession with strains Ian Bollinger, the scientist who originally developed the testing protocols for the aforementioned Hyphae Cup said this on a recent episode of the Hyphae Leaks podcast:

[Potency] has less to do with the strain itself and more to do with the supporting of the strain. The three major factors that go into a potent mushroom are how you cultivate it, its genetics, and furthermore how you treat it afterwards.

You’ll notice only one of those factors are linked to genetics, which as we discussed earlier is a difficult concept to pin down for strains. Focus on good cultivation technique and post-harvest preservation, and you’ll be working with the potency-enhancing factors you have better control over.

Once you’ve got a few grows under you belt, look to different species, not strains, for a way to learn new techniques or for higher potency. Following the domestication theory, wild woodlovers like Psilocybe cyanescens seem to laugh in the face of contamination and many are considerably more potent than our precious Psilocybe cubensis, making them a great low tech alternative that can even be grown outdoors in the right climate.

Until we hear science say otherwise, we’re going to continue to be skeptical of the hype around magic mushroom strains. The work of some strain breeders is certainly impressive, generating some beautifully weird results—however we can’t help but think of the poor purebred bulldog with its cute face but terrible breathing problems and hip dysplasia, and wonder how these poor deformed mushroom feel. We find learning about good growing and harvesting technique, and the other species of less domesticated magic mushrooms far more fun, and we’d encourage you to do the same!

*There may be another explanation here. It could be that the samples lost considerable potency during the drying or analysis process. We’d probably need more data on this to know for sure, but given the general potency data from the Hyphae Cup matches that found in published scientific studies, this may be unlikely.

er.

So those strains that lack the ability to sporulate (like Enigma, for instance) would be the fungal equivalent of a liger!? Great read, looking forward to an article discussing the absurdity of the taxonomic naming system to begin with